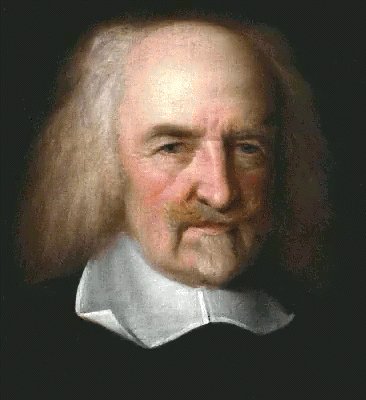

The discussion of norming in the last post leads to an interesting question that isn’t really settled among Hobbesian thinkers: was Hobbes himself a racist? We have seen how modern scholars have used Hobbes to explain ingrained racism, but it isn’t clear that Hobbes intended that. The question is complicated further because ‘race’ as we know it wasn’t really operative in Hobbes’ time. People saw the world not as ‘black and white’ but more so as ‘civilized and uncivilized.’ Because of this, accusing Hobbes of racism may not be fair at all. But let’s put that aside ask again: Is Hobbes racist?

Clearly, he had unflattering things to say about the “savage peoples” of America. He thought that they were lesser because they had not escaped the State of Nature. Hobbes did not directly address race in the Leviathan so it is not clear if he believed skin color was a factor in intelligence, civility, etc., but we have seen how modern thinkers have used Hobbesian Social Contract theory to explain the roots of bias by way of norming. Still, even if we grant that norming does occur, is that enough to say that Hobbes was personally racist?

Hobbes didn’t write much on race, but he does cover slavery in the Leviathan. And as Hobbes is wont to do, he explains it with a theory of contracts. He distinguishes between slaves and servants, and says that servants have an implicit or explicit contract with the Master, which differentiates them from slaves. Here’s the quotes from Chapter 20 of the Leviathan:

“And this dominion [over the individual] is then acquired to the victor when the vanquished, to avoid the present stroke of death, covenanteth, either in express words or by other sufficient signs of the will, that so long as his life and the liberty of his body is allowed him, the victor shall have the use thereof at his pleasure. And after such covenant made, the vanquished is a servant, and not before…”

The covenant (contract) is this: the master agrees to spare the life of the slave, and the slave agrees to serve the master as he wishes. Once the contract is established, the slave is considered a servant. A slave can only be called a slave when he is held against his will and is actively trying to escape his bondage. The key to understanding Hobbes’ views on slavery is the phrase ‘conquest is contract.’ Hobbes believed that contracts are valid even if they are initiated by conquest and enforced by physical force. In the modern world, common sense—and certainly courts of law—would not accept a contract that was made with a gun to one party’s head.

Additionally, Hobbes’ conception of slavery seems at odds with the modern idea of slavery. Hobbes would say that slaves remained on plantations because they agreed to be there in exchange for their lives. But really, aren’t slaves only working on the plantation because not working would put their lives in danger? They haven’t agreed this that arrangement at all! Hobbes would counter that if the slaves are not actively rebelling then they have, in fact, tacitly agreed to serve the master. Through this reasoning, Hobbes justified slavery. But still, it is not a racially motivated account of slavery, leaving our question still unanswered.

Although Hobbes referred to indigenous American peoples as “savage” and found a justification for slavery in his theory of contracts, there is evidence for the other side of the question as well. Perhaps among the most compelling is the fact that Hobbes went out of his way to organize his theory so that it didn’t require a religious or racial justification. There is absolutely no evidence that Hobbes believed a contract is any less binding when people of minority races are party to it. Hobbes’ writing is neutral in that respect.

It is also import to remember that at its core Hobbes’ Social Contract is egalitarian. The opening paragraph of Chapter 13:

“Nature hath made men so equal in the faculties of body and mind as that, though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body or of quicker mind than another, yet when all is reckoned together the difference between man and man is not so considerable as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit to which another may not pretend as well as he. For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination or by confederacy with others that are in the same danger with himself.”

It’s “all men are created equal” without Jefferson’s brevity. This premise is a necessary basis for Hobbes’ contracts-based view of the world, because if men were unequal they couldn’t make valid contracts with each other. So, it is possible that because black slaves could form a contract with their masters, Hobbes believed they were equal to other men.

So, what’s the verdict?