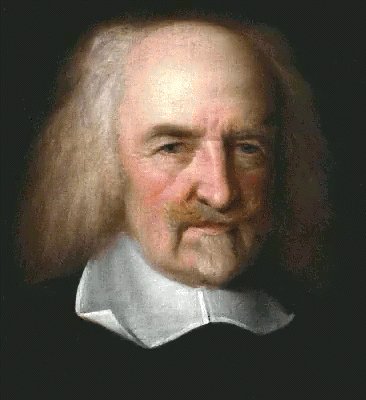

Seinfeld was a show about nothing. The State of Nature, as Thomas Hobbes saw it, is also a show about nothing. He argues that there is no way for people to develop anything physical or cultural in the State of Nature, leaving them with nothing except their person to defend. In the quote below, from Chapter XIII of the Leviathan, Hobbes lists all the things that could not exist in a State of Nature.

In [the State of Nature] there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. (Leviathan, Part 1, Chapter XIII, paragraph 9)

That’s a whole lotta nothing. Hobbes feels that in the State of Nature, people would be constant enemies, so they could never develop relationships, share ideas, or build communities. This is no way for humans to live, and Hobbes said that we would come to together to form the civil society to escape this.

An aside: This is probably the most famous paragraph Hobbes ever wrote. The final line has been paraphrased over and over, and is often misunderstood to be Hobbes musing on the nature of human existence. More accurately, it is how Hobbes describes life in the every-man-for-himself war that perpetually exists in the State of Nature. Nevertheless, it is the line that permanently typecast Hobbes as the pessimistic foil to John Locke’s utopian State of Nature.

Back to the main event: Why couldn’t people ever join together in the State of Nature? Self-preservation. Hobbes says we have an unlimited right to self-preservation. In the State of Nature we have no allegiances, no obligations to our fellow man, no laws, no incentive at all to cooperate with other people. If, for example, I built a shelter, I would never share it with you because your existence is a threat to my self-preservation. In fact, we both have a right to kill each other in order to get the shelter. In Hobbes, self-preservation is the only right we have in the State of Nature.

But wait! Couldn’t forming alliances with other people actually work toward self-preservation (teaming up to defeat a more powerful enemy, perhaps)? It could, but even if these alliances did occur in the State of Nature, they would quickly dissolve and the participants would turn on each other as soon as the goal was accomplished. Why? Because of what Hobbes calls “diffidence.”

There are “three principle causes of quarrel.” The first is competition, as humans as naturally competitive; the second is diffidence, which is important to this post; and the third is glory, since humans are concerned with reputation. Diffidence is the reason men cannot form alliances in the State of Nature. The word has changed meaning somewhat since 1651. Today it refers to a lack of self-confidence, shyness, etc., but Hobbes used it to mean “distrust of others; insecurity in one’s possessions.” This insecurity is critical to understanding fear in Hobbes.

We are in constant fear of having our possessions taken, so we proactively conquer others to prevent that. Hobbes notes the centrality of fear to the State of Nature in the quote at the beginning of this post. He lists all the things humans couldn’t create in a State of Nature, then concludes, “and, which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death.” He states that constant fear in the State of Nature is the worst part of the State of Nature. With no Social Contract, people live in a unending war in which we constantly fear having our possessions taken by force, so all of our actions seek to prevent attacks by others. Therefore, fear is the driving force behind all actions in the State of Nature. Check out this syllogism to sum it up:

- The State of Nature is a State of War

- The State of War is a State of Fear

Therefore: The State of Nature is a State of Fear

Finally, let’s get down to brass tacks. How is all this useful in analysis of the world today? This site will use Hobbes ideas about the State of Nature to explain current events. Although we don’t live in a state of Nature, Hobbesian ideas about fear are still relevant. A basic tenet of the analysis on this site will be that the State of Nature is active in the world today and that fears of immigrants/minorities/women/whatever are driven by an underlying fear of the State of Nature. Here’s why:

In the modern world, no one physically lives in a State of Nature. BUT we know that we have formed a society to get away from the State of Nature. So, when something conflicts with the social organization that we are comfortable with, we try to suppress it. In the State of Nature we would use force, but now we use tactics like politics, law, discrimination, and social norms. We are trying to defend our society because we fear the State of Nature. This is my ultimate contention that will recur across this site: that fear of the State of Nature is an explanation for discrimination based on race/sex/nationality/sexual orientation/economic class.

In today’s world, society uses discrimination as a defense mechanism. We want to defend our “possessions” (in the form of culture, jobs, tax dollars, whatever), but instead of by force as in the State of Nature (although sometimes by force) we use discrimination.

The State of Nature is nothing concrete, it is whatever it is perceived to be. It has no set place, no actual members, no physical presence. Nothing to point to directly. That is partly why we attach the State of Nature to outsider groups. It is largely a human construction that has no true being. Nevertheless, the State of Nature is real and active in our world, driving the plot. For a ‘show about nothing,’ it’s really something.

Leave a comment on this post and tell me what you think about fear as a cause of social actions and about the State of Nature lurking in society.

COMING MONDAY: Is Hobbes racist? and the mechanism by which we ascribe the State of Nature to ‘other’ groups